It’s easy to forget Doc Gooden was only 31 when he signed with the Yankees prior to the 1996 season. He broke in with the Mets at age 19 and was a sensation. George Steinbrenner wanted a 19-year-old stud of his own, which led to Jose Rijo being brought up in 1984, but that didn’t work out too well. Gooden was a star in the 1980s and the Mets were the toast of New York.

By 1990 things had turned south for the Mets and Gooden. He had drug problems and got hurt, and his performance suffered. Gooden was suspended 60 days after testing positive for cocaine in 1994, then, while serving the suspension, he tested positive again. MLB suspended him for the entire 1995 season. Gooden threw 41.1 total innings from 1994-95 — his age 29-30 seasons — due to the suspensions.

The Boss loved giving second chances and he loved needling the Mets. Gooden’s suspension ended on October 1st, 1995, and he threw for scouts shortly thereafter. The Yankees signed him almost immediately. Steinbrenner gave Gooden what amounted to a one-year contract with two option years. He would be paid $1M in 1996, then $2M in 1997 and $3M in 1998 should the team decide to keep him.

The contract was rather complicated because of Gooden’s history, and in fact it did not become official until February. Per the terms of the deal, Gooden had to be drug tested three times a week and stay in a 12-step program. Steinbrenner said he was “very impressed with the sincerity of Dwight’s commitment to restructuring his life” in a statement. “Being a Yankee is a dream come true for me. A year ago, I hit rock bottom. Now I’m a Yankee,” said Doc to Jack Curry.

Gooden joined David Cone, Jimmy Key, Andy Pettitte, and Kenny Rogers in the 1996 Opening Day rotation. Gooden started the fourth game of the season and it did not go well. He allowed five runs in five innings against the Rangers. Six days later he allowed six runs in 5.1 innings to that same Rangers team. Six days after that Gooden allowed six runs in three innings against the Twins. He allowed 17 runs and 33 base-runners in his first 13.1 innings of 1996.

The Yankees temporarily moved Gooden to the bullpen and gave Scott Kamieniecki a spot start. There was also talk of sending him to the minors for more work after he missed the entire 1995 season and barely pitched in 1994. That didn’t happen. Gooden never did pitch in relief but he did go a week between starts in late-April. On April 27th, in his fourth start of the year, he held the Twins to one run in six innings. He struck out seven.

With that start, Gooden had earned his way back into the rotation. Of course, David Cone came down with his aneurysm a few days later, so Gooden was likely headed back to the rotation no matter what. He threw six shutout innings against the White Sox on May 3rd, albeit with more walks (six) than strikeouts (four), then held the Tigers to two runs in eight innings on May 8th. That was three very good starts in a row after three ugly starts to open the season.

The Yankees were at home on May 14th, a Tuesday, and the Mariners were in town for a quick two-game series. New York had lost three of their last four games and needed Gooden to stop the bleeding. The Mariners had baseball’s best offense — they scored 993 runs in 1996, 32 more than any other team — led by Alex Rodriguez, Ken Griffey Jr., Edgar Martinez, and Jay Buhner. The lineup they sent out that night was nutso.

- Darren Bragg — 110 OPS+ in 1996

- A-Rod — 161 OPS+

- Griffey — 154 OPS+

- Martinez — 167 OPS+

- Buhner — 131 OPS+

- Paul Sorrento — 121 OPS+

- Dan Wilson — 95 OPS+

- Joey Cora — 91 OPS+

- Russ Davis — 74 OPS+

The bottom of the order wasn’t so bad, but spots one through six? Forget it. Murderer’s Row. Seattle had Hall of Fame caliber hitters batting second, third, and fourth. It’s no surprise the game started ominously for Gooden. He walked Bragg to leadoff the first inning, then Rodriguez ripped a line drive to center field that miraculously turned into a double play. Check it out:

Gooden walked a batter in the second inning and another in the third inning before really settling down. He retired seven in a row and 16 of 17 after the third inning walk. (The one base-runner came on a Tino Martinez error. He bobbled a ground ball at first base.) After eight innings and 109 pitches, a 31-year-old but very much not in his prime Doc Gooden had held the juggernaut Seattle offense hitless.

Without looking back at the play-by-play of every no-hitter in history, I’m guessing the ninth inning of Gooden’s no-hitter against the Mariners that night was one of the toughest final innings of a no-no in baseball history. I remember watching the game live and it was so very clear Gooden was out of gas. He was running on fumes. The Yankees led 2-0, so the game was close, yet John Wetteland had not even warmed up before the start of the ninth.

The first batter of that ninth inning, A-Rod, drew a six-pitch walk after Gooden jumped ahead in the count 1-2. Griffey ripped a ground ball that Tino grabbed, then dove headfirst into first base to get the out. “It was the only way I could get him,” said Martinez to Curry after the game. Edgar Martinez followed with a six-pitch walk to put the tying run on base. Gooden’s first pitch to Buhner skipped away from catcher Joe Girardi, allowing the runners to move. Now the tying run was in scoring position with one out.

The game was very much on the line now. Gooden had thrown 125 pitches up to that point and there was nothing in the tank. Wetteland had started to warm in the bullpen, but by that point it seemed moot. The speedy Rich Amaral pinch-ran for Martinez at second base, so Gooden was either going to complete the no-hitter, or he was going to give up the game-tying base hit. There was no middle ground.

Jay Buhner was at the plate, and Jay Buhner was one of the most menacing looking dudes who have ever played the game. Plus he always torched the Yankees. He made them regret the Ken Phelps trade every chance he could get. Gooden fell behind in the count 2-1 to Buhner, then was able to pick off the corner with a fastball for strike two. On his 130th pitch of the night, Doc threw a fastball by Buhner for strike three. That was … unexpected.

Gooden was one out away from the no-hitter, yet danger still loomed because the tying run was at second base. Paul Sorrento was the batter, and he swung through the first pitch of the at-bat for strike one. Gooden missed with the next two pitches and was again behind in the count 2-1. If not for the no-hit bid, Doc would have been out of the game long ago, and the now warm Wetteland would be on the mound. History was made on Gooden’s 134th pitch of the night.

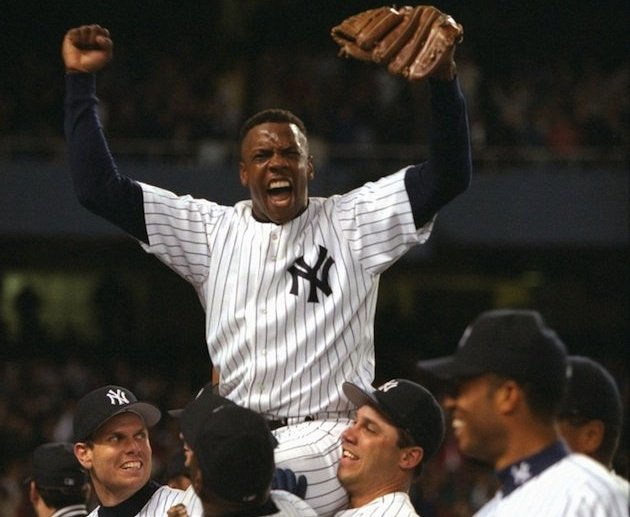

“(The final out), it’s something that just goes through you. I can’t describe it. It’s something that happens. I never had it before,” said Gooden after the game, after Griffey interrupted his press conference to give him a hug. “In my wildest dreams, I never could have imagined this. This is sweet.”

Gooden threw 134 pitches in the no-hitter, and he did it while knowing his father would undergo open-heart surgery the next day. “Hopefully he knows about it,” said Doc, who left the team after the game to go home to Florida to be with his father. “You’ve seen a guy have a second chance with his career,” said Torre after the game. “It’s so satisfying.”

The rest of the season did not go so well for Gooden — he had a 5.19 ERA in 22 starts and 128.1 innings after the no-hitter — and he was left off the postseason roster. For that one night in May, less than two months after returning from close to a two-year layoff, Doc was on top of the baseball world, having thrown a no-hitter at Yankee Stadium.

“I think this is the greatest feeling, especially because I did it in New York,” he said. “With all I’ve been through and all the stuff that has gone in, this is the greatest feeling.”